The Biological Basis of Trauma: Part 2: Trauma’s Effects on Development

This blog is the second in a three-part series delving into the biological basis of trauma. The purpose of this series is to help develop insight into how trauma affects us, so that we can understand how to work with the havoc it has wreaked in our lives. Remember as you read this series, this is not an unchangeable tale of doom. If you are alive, you have the potential to change your narrative. Yes, trauma does change us. Our minds and bodies developed to survive dreadful, violent realities. So, yes, we are different. But different does not mean defective. So use this information to help you understand the demons you tango with, so that you can move forward in creating the story you want to live!

If you’ve read the first blog in this series, you will know that a traumatic event can change how your body responds to the world. But what happens if that traumatic event happens during childhood, when the brain (and body) is developing and learning the basics of functioning? Or, even worse, if multiple events happen again and again throughout childhood, throughout the entire developmental process?

As we all know, the childhood brain and body are highly malleable. Our genetic programming assumes that the events we encounter during childhood will be similar to those we encounter in adulthood. This assumption means that our bodies are shaped to meet the stressors and requirements of our childhood. If our childhood happens to be traumatic, then our very being will be designed on the assumption that life is a threat to our survival. Trauma will be the forging fire that defines us.

But what exactly does this mean? How exactly is trauma shaping us biologically? Essentially, trauma is influencing three major things: the structure of our brain, the functioning of our physical selves, and the genes that are expressed.

Trauma and the Structure of the Brain

Trauma can alter the very shape of our brain. If you are under the impression that trauma causes only superficial adaptations, think again. Individuals that experience trauma throughout their childhoods have brains that are physically different from individuals who did not. Portions of the brain critical to executive functioning, emotional regulation, and self-referential processing are smaller, less developed.

Executive functioning includes things like the ability work with information without losing track of what we are doing, being flexible in our thinking, and generally having self-control and not giving in to every impulse we have. Emotional regulation is, exactly as it sounds, the ability regulates and control our emotions. And self-referential processing is essentially introspection and the ability understand yourself and how the world affects you.

When areas that are critical to these functions are underdeveloped, it means the person is simply not as capable of performing the required tasks. Imagine if your arm were placed in a cast for years, the muscles never really used, never really developed. Finally as an adult, the cast is removed. Even with physical therapy, it’s possible that the damage done to your arm is so significant you will never be able to use it as others. This is what trauma does to the brain, it stunts certain portions so effectively that even with years of reprogramming, therapy, and self-work it may never function as other brains do. (Don’t give up hope, though! This doesn’t mean you’re broken, just different!)

Trauma and Physiological Functioning

Trauma during childhood also, of course, changes how our brain and body function. When we experience trauma, our bodies and minds believe that we are being exposed to stimuli so severe they may end our lives. Essentially, the trauma/fear response is our bodies attempts to survive. Being repeatedly exposed to trauma, means you are continuously in survival mode.

Remember, development is about changing the body and brain to meet the demands of the world. Part of this involves identifying the optimal levels of hormones and neurochemicals for our bodies. In essence, throughout our childhood, our bodies are creating what “normal” should look like. Once this “normal” is set, our bodies fight to keep it.

This fight is called homeostasis. Homeostasis involves tons of physical processes that are constantly working to keep our body balanced. For example, when it gets hot out, our bodies sweat. This is an attempt to keep our optimal temperature. Homeostasis is wonderful, because it keeps us balanced and functioning, instead of constantly falling apart. But what happens, though, if your body believed that your optimal temperature should be 120 degrees? We;;, what happens is your body will fight to maintain you at 120 degrees, even if it damages the rest of you.

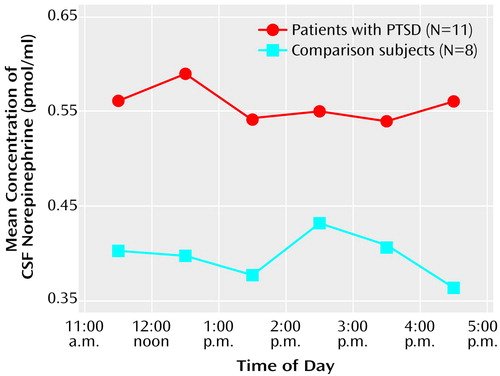

This is similar to what happens with childhood trauma. When exposed to trauma during our development our balance points, through years of training, are set to allow us to survive a hostile environment. The amount of cortisol, nor-epinephrine, serotonin, GABA, all of our hormones and neurochemicals and body systems get set on survival. This means that homeostasis is now fighting to keep us in survival mode. Our bodies believe that constantly having adrenaline and cortisol pumping through our system is necessary. So if we begin to calm down, and those levels drop, our bodies will fight to bring them back up and make us tense. It is possible to change this with work, but it is often very difficult. After all, imagine trying to change your optimal temperature from 98.6 to even 99.6.

Trauma and Genetics

One last way that childhood trauma affects us is through epigenetics. Essentially epigenetics is all about what genes are activated and which ones are not. Contrary to popular belief, our genetic programming is not a story written in stone, a fate that can’t be altered. Instead, many of our genes are simply potentials. The potential to have diabetes or not to, the potential to have schizophrenia or not, the potential to be tall or short. It is our environment, in part, that decides on this potential.

Traumatic environments are ugly environments. They require a lot of a person to survive them. When we grow up exposed to trauma, our potential is, in part, decided by this trauma. The potential that will help you survive is what is activated. This may seem weird given the fact that the genetic potentials that are activated in trauma often result in significant mental and physical health problems. But survival doesn’t care about the long game. Survival cares about now. And so the potentials you need to survive get activated. Often, in a “normative” or healthy environment, these expressions make no sense. But place them in the context of the trauma that fostered them into existence, they make perfect sense. In fact, all of the effects of trauma on development, make a lot of sense when you realize your mind/body/genes were simply doing their best to help you survive the trauma filled world of your childhood.

Resources

https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/disease/epigenetics.htm

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41398-021-01357-z

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3968319/